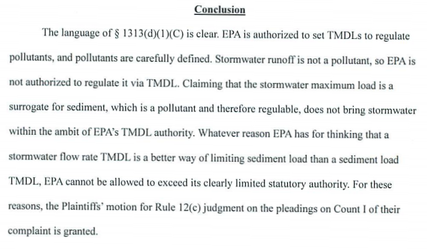

The EPA has the authority to set "total maximum daily loads" (TMDL's) on pollution that degrades water quality. But the court made it clear that there's a distinction between setting a limit on source pollution and its means of transport. EPA's legal problem in this case was that they were treating water itself like a pollutant.

In a nutshell, the State of Virginia argued that EPA has no authority to regulate stormwater volume since stormwater without any pollutants is not a pollution source. (And EPA has no authority to regulate things that are not a pollutant or pollution sources.) The Attorney General who fought the case explained it here.

EPA has tried to regulate many things based on the presumption of an impact, but if there is not actual impact by the “delivery system” (water) that might carry pollutants, its jurisdiction is questionable. It was a valid argument, and it won. Here’s the judge’s rationale, exactly as published:

The Lake Whatcom situation provides a perfect example of how a bad approach to science – poor theory -- gets memorialized by regulators. The Department of Ecology's TMDL's for Lake Whatcom rely on model data using a program called ESPF, that uses a primitive fate-and-transport model to conclude that residential development is the source of most of the phosphorus in the lake. WA Ecology's 2008 Lake Whatcom TMDL "Water Quality Study Findings" report repeatedly states that it employs "surrogate measures" to regulate pollutants.

So, TMDL's here are based on model, not observed, data and stormwater is a surrogate (a substitute, or “proxy”) for pollutant (phosphorus) sources. This is very similar to the case decided in Virginia. In Virginia, the pollutant was "sediment," and here the pollutant is "phosphorus."

The preliminary Lake Whatcom TMDL study's conclusions were careful to include strong recommendations for additional tributary monitoring and additional studies of the contribution of phosphorus from developed properties. But those recommendations have been only partly followed.

Water quality measurements are taken, true - but the necessary identification of the sources and impacts of the pollutants that stormwater actually carries (fate and transport) have not been conducted. Yet Ecology staff continues to feed water quality data into a model with circular dependencies, claiming that these results confirm the Institute for Watershed Studies conclusions.

As for phosphorus input to the lake, Ecology has estimated that the City of Bellingham's diversion from the Middle Fork of the Nooksack River contributes 300 Kg of phosphorus into the lake every year. The City acknowledges this phosphorus contribution, but asserts that most of the phosphorus sinks to the bottom of the lake and does no harm. That assertion needs to be proven.

Regulators here have been using a shotgun approach by damning stormwater in general. Using the model may be a convenient "tool" for Ecology, but its results are invalid (and the TMDL's are moot) if causes and sources aren't properly studied.

Biochemistry has established that most phosphorus in the environment occurs naturally. Therefore saying, "Where there's development, there's more phosphorous" is absurd. This is particularly true because phosphorus-bearing products aren't being used nowadays; they were banned in the watershed in 2005. Failing to thoroughly specify and quantify the sources of phosphorus around the lake is not only bad ecological science, Ecology's failure to prove the connection between sources and pollutant TMDL's could be downright negligent.

As for the Virginia case, EPA does not like losing in court. It has an endless supply of taxpayer money, and it’s likely that the agency will continue to fight the State of Virginia. But for the moment, this is what it is – a big win for science and reason.

More about the case can be found at the Virginia Attorney General's webpage. Here’s a clip:

"EPA had previously issued an edict that would cut the flow of water into the creek by nearly half, in an effort to address the sediment flow on the bottom of the creek. In regulating the flow rate of stormwater into the creek, the agency was trying to regulate water itself as a pollutant, rather than the sediment. The attorney general challenged the EPA's action as exceeding the agency's legal authority to regulate pollutants under the Clean Water Act (CWA). These restrictions also would have diverted public funds that could be spent more effectively on stream restoration for Accotink Creek and other waterways in the region.

Judge Liam O'Grady agreed with co-plaintiffs VDOT (represented by the attorney general) and Fairfax County, saying in his ruling that federal law simply does not grant EPA the authority it claims. The Clean Water Act gives the EPA the authority to establish TMDLs - Total Maximum Daily Loads - regulating maximum acceptable levels of pollutants that may be discharged on a daily basis into a particular waterway. The problem for the EPA is that water is not a pollutant under the CWA. "The Court sees no ambiguity in the wording of [the federal Clean Water Act]. EPA is charged with establishing TMDLs for the appropriate pollutants; that does not give them the authority to regulate nonpollutants," O'Grady said.

"EPA's thinking here was that if Congress didn't explicitly prohibit the agency from doing something, that meant it could, in fact, do it," said Cuccinelli. "Logic like that would lead the EPA to conclude that if Congress didn't prohibit it from invading Mexico, it had the authority to invade Mexico. This incredibly flawed thinking would have allowed the agency to dramatically expand its power at its own unlimited discretion. Today, the court said otherwise."

EPA also claimed that it could regulate water flow because it was a surrogate measure for regulating sediment. To that argument, Judge O'Grady responded, "EPA may not regulate something over which it has no statutorily granted power... as a proxy for something over which it is granted power." He continued, "If the sediment levels in Accotink Creek have become dangerously high, what better way to address the problem than by limiting the amount of sediment permitted in the creek?"

"Stormwater runoff is not a pollutant, so EPA is not authorized to regulate it," O'Grady said.

"EPA was literally treating water itself--the very substance the Clean Water Act was created to protect--as a pollutant," the attorney general noted. "This EPA mandate would have been expensive, cumbersome, and incredibly difficult to implement. And it was likely to do more harm than good, as its effectiveness was unproven and it would have diverted hundreds of millions of dollars Fairfax County was already targeting for more effective methods of sediment control."

A copy of the court's opinion can be found here.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed