WE respect the depth of intellectual rigor of the founding. In candle-lit times, the prerequisite education to enter colonial colleges (Harvard (1636) and William and Mary (1693)) was daunting by today's standards. And while it's true that George Washington didn't have the luxury of such a formal education, his talents, curiosity and practical interests were tremendous. Understand not only the making of this man but the bold intellectual nature of the American Revolution, itself. Read on.

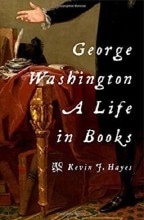

A bibliographical view of the Father of Our Country.

By Douglas Bradburn, July 3, 2017

The Weekly Standard

Thomas Jefferson also opined on the scholastic achievements of George Washington and noted that Washington read “little.” He did assert that Washington possessed a powerful mind, but it was not quite first rate. George Washington, Jefferson concluded, “was not so acute as” Sir Isaac Newton, Francis Bacon, or John Locke—a pretty lofty standard. So where does Washington fit? Somewhere between illiterate and Sir Isaac Newton.

Historians have typically been rather cool on Washington’s reading and learning, echoing Adams and Jefferson. Some have even argued that his best letters were written by someone else—Broadway’s Alexander Hamilton comes to mind—and compared with the constellation of geniuses present at the founding, Washington is sometimes seen as but a dim star, even though he looked great on horseback. The great historian James Flexner argued that the “indispensable” George Washington was the ultimate man of action, but “only a sporadic reader.”

It is true that Washington did not have a formal education of the type expected of a gentleman of his era. Adams and Jefferson both went to college, Harvard and William and Mary respectively. (Washington would later receive an honorary doctorate from Harvard and serve as chancellor of William and Mary.) To gain admittance to either school in the 18th century, one needed to be able to read Latin. Once there, the young scholars embarked upon a rigorous study of classical literature in the original Latin, Greek, and Hebrew, they learned rhetoric, logic, divinity, physics, and metaphysics, as well as algebra and astronomy. To become lawyers, both Jefferson and Adams then read law extensively under the guidance of a master attorney until they were ready to pass the bar.

Washington, for his part, didn’t have these opportunities. His two elder half-brothers had been educated in England, but after the death of his father in 1743 when young George was 11 years old, such an expensive elite education was out of the question. He would have tutors of various competency, but for the most part, he would be on his own. George Washington, like Benjamin Franklin, was self-taught.

At age 17, he was a professional surveyor; at 22, an age when Jefferson and Adams were reading law, Washington was the colonel of a Virginia regiment, fighting in the French and Indian War. As Hayes emphasizes, at that age George Washington had already written a book—a short journal describing his harrowing mission to the Ohio Country in the middle of the winter of 1753-54, when he was sent by the governor of Virginia in Williamsburg to explain politely to the French Army near Lake Erie that they were trespassing on Virginia’s land. Filled with Indians, bear-hunting, diplomatic intrigue, a flight across a frozen river, intrepid pioneers, and an impossible and unforgiving wilderness—think The Revenantwith a happy ending—the small book was widely read in England and serialized across the American colonies. The adventures of Major Washington helped precipitate a diplomatic crisis and made George famous on both sides of the Atlantic. He was an 18th-century reality star.

As a reader, Washington consumed all he could—in English. He bought and borrowed books of all kinds: travel and adventure stories (not unlike the one he wrote), geographies and atlases, his father’s copy of Shakespeare’s plays, encyclopedias and dictionaries, picturesque novels, treatises on military science, histories both ancient and modern, politics, agriculture, and law. And he would regularly devour the most recent available newspapers. As a young man on the make, he would spend hours in the fine library of his patron and neighbor, Col. William Fairfax, and discover to his surprise (long after the old man had died) that he had forgotten to return William Leybourn’s Complete Surveyor.

Washington was particularly fond of the new magazines that became available in the Anglo-American world in the 1730s and ’40s. These works, like the Gentleman’s Magazine, collected news and literature, scientific reports, histories, metaphysics and philosophy, political satire, clever anecdotes, short stories and poetry, and were a sort of compendium of miscellaneous information—the broad sweep of human learning. As a young man Washington showed a particular interest in poetry, even trying his hand at love poetry in a stumbling attempt to unlock the mysteries of an unknown young woman’s heart.

But nothing eclipsed his early interest in mathematics. Here Washington showed exceptional talent; in fact, one gets the sense that he had an easy gift combined with the profound appreciation of the logical beauty of a good proof. In his copy of Archibald Patoun’s Complete Treatise ofPractical Navigation Washington corrected a mistaken example of how to calculate the declination of the sun—crucial to discovering one’s location on the globe. In his spare time while president of the United States, he designed a unique 16-sided threshing barn and calculated the exact number of bricks needed in construction. Mathematics had a practical purpose for Washington: It was useful for his surveying profession and essential for his agricultural and military pursuits; but he pursued the study for his own pleasure. At 18, he purchased Guillaume François Antoine de L’Hôspital’s Analytick Treatise of Conick Sections, a work of advanced geometry, something which had little practical purpose other than to satisfy his eager, hungry, and curious mind.

John Adams, for his part, was terrible at math.

When he realized that he had not read certain books that his peers considered essential, like the novels Gil Blas and Don Quixote, he purchased them and quickly began referencing them in his own correspondence. In one delicious case, in James Monroe’s published defense of his behavior as American minister to France, Washington made extensive, sarcastic, and biting notes, ridiculing Monroe’s pretensions to authority, clarity, honesty, and competence. His running critique of Monroe would have played well at a White House Correspondents’ Dinner.

During the Revolutionary War he had a special bookcase designed, complete with green baize lining to protect a large collection of military books that accompanied him throughout the war—from Valley Forge, to West Point, to Yorktown. As mentor of the inexperienced officer corps of the Continental Army, he recommended reading specific titles to the unsure and unsteady. He had long practiced what he preached: During the French and Indian War, when he was in charge of the frontier defenses, he traveled with Caesar’s Commentaries and Quintus Curtius’s History of the Wars of Alexander the Great. Washington’s example made an impression: One Hessian officer was astonished during the war that “every wretched knapsack” of a captured American officer was “filled up with military books.”

At the end of the war Washington’s fame and consequence would put him in a position of patronage. The first histories of the American Revolution, as Hayes shows, depended upon Washington’s papers and his support. It was myth-making from the start, and with Washington’s support for painters, sculptors, poets, historians, and authors, the United States began to make its own mark on the republic of arts and letters.

One advantage of Washington’s self-directed education and lifelong curiosity was reflected in his willingness to change his mind or reject received opinion for new ideas. Hayes reveals this aspect of Washington’s mind by exploring the ultimately profound shift in his ideas about slavery. Born into a slave society and an owner of people his entire life, Washington collected anti-slavery pamphlets and tracts, and gradually came to shift his own perspective. By the time he became president he was privately asserting his desire to end his commitment to enslaved labor, a problem he never solved until his death. He would use his last will and testament to provide a pathway for freedom for the slaves he owned outright, providing for the education of the young and pensions for the elderly. And he wrote his will without the aid of lawyers.

Kevin J. Hayes’s study will reward the reader with a newfound respect for our first president and imparts a renewed sense of the sustained curiosity of truly great leaders. It is a book even John Adams might have enjoyed.

Douglas Bradburn is founding director of the Fred W. Smith National Library for the Study of George Washington at Mount Vernon.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed